Twee maal een onzichtbare hand: gedachtegoed

Samenvatting

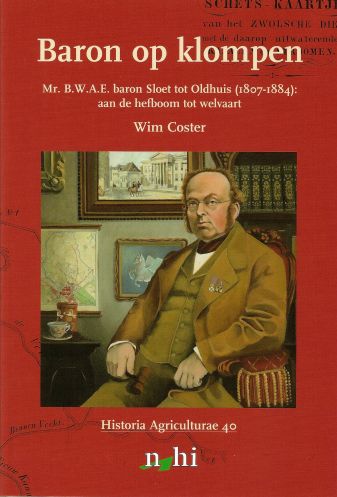

Chapter 3, ‘Twee maal een onzichtbare hand’ (‘Twice an invisible hand’), elaborates on Sloet’s intellectual baggage. His thoughts appear to have been guided by two invisible hands: that of religion and that of economy, while Classic Antiquity also took up a prominent part of this baggage. In his religious life Sloet was guided by ‘physico-theology’, a school of thought which originated during the age of Enlightenment and was based on the idea that the forces of nature refer to a Creator. Other physico-theological writers, such as J.F. Martinet (1729-1795) wanted to convince their readers of the existence of God and his lasting care for his Creation on the strength of the available knowledge of natural phenomena. They wanted to point out that Nature is organized in such a systematic and functional way that a Nature without God simply cannot exist. What is more they summoned everybody to get to know and admire the magnitude of the Creator by means of the investigation of Nature. This way of thinking is based on both rational proof of God’s existence and the visible manifestation of God’s power, wisdom and goodness in the cosmic order of things. In accordance with the empirical spirit of the times this last aspect was emphasised most in the eighteenth century. Although a man of the nineteenth century, empiricism fitted Sloet like a glove. According to Sloet morality was closely connected with religion in defining morals, norms, values and (therefore) citizenship. From morality to political economy was another small step as far as Sloet and many of his contemporaries were concerned. Within this context statistics and rural economy were also important and Sloet was certainly intensively engaged in these matters. The pillars of his world view and thoughts on people’s happiness -in the sense of material and non-material prosperity- were therefore a mixture of classic, Christian and profane materials. Chapter 3 explores the composition of this mixture. As Hans Boschloo quite rightly states in his work De productiemaatschappij, in 1848 Sloet was ‘just like almost every other ‘laisser faire’ economist probably a Thorbeckian’. However, over the years he found himself more and more estranged from the liberal mainstream. In his eyes liberalism brought too much state interference, which was harmful to regional autonomy and resulted in unnecessary bureaucracy, his two largest frights. Because where could personal interests be served better than in one’s own immediate surroundings? And why should civil servants in The Hague interfere with the life of a farmer in Overi336 jssel? Sloet considered freedom and centralisation to be opposites. This does not mean, that he was against any form of state interference, except where it concerned the care for the poor or the non-productive citizens. In that case he adhered to the principle: ‘he who does not work shall not eat’, although he would not say so outright. For Sloet – who was after all a lawyer – the form of government was less important than the general Christian state family in which everybody knew his place and lived by the same unwritten rules and principles, while fulfilling a task in order to provide for his or her livelihood. The next four chapters show how Sloet operated, being guided by this way of thinking.Gepubliceerd

2009-07-03